Rethabile Pitso

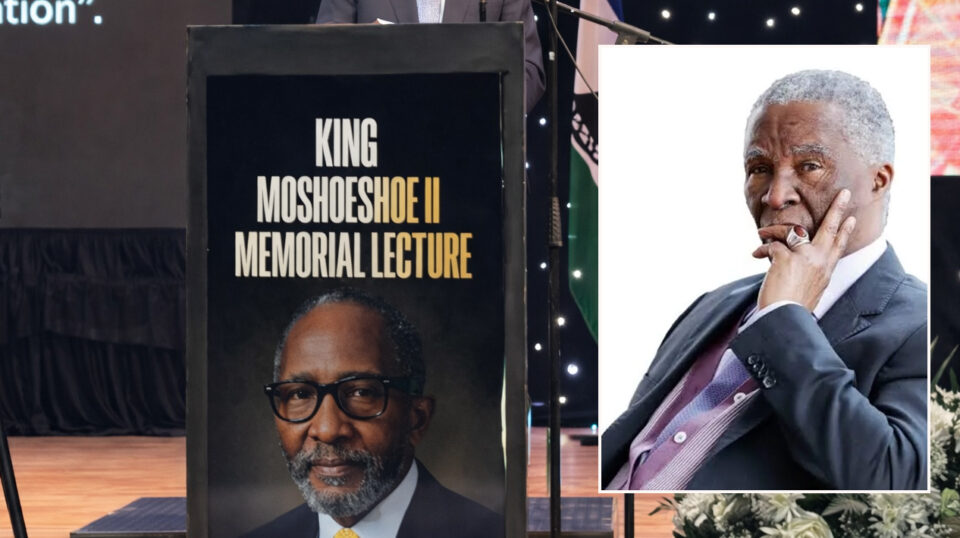

FORMER South African President Thabo Mbeki has delivered a powerful lecture in honour of the late King Moshoeshoe II, marking 30 years since the monarch’s passing.

The commemorative lecture, held in Maseru yesterday evening, was attended by members of the Royal Family led by His Majesty King Letsie III, cabinet ministers led by Prime Minister Sam Matekane, and a host of distinguished local and international dignitaries.

King Moshoeshoe II died on 14 January 1996 in a car accident.

In his keynote address, Mr Mbeki presented an extensive and deeply insightful account of King Moshoeshoe II’s legacy, portraying him as a committed Pan-Africanist who never wavered in his quest to liberate the Basotho from the grip of colonialism.

Mr Mbeki said the late king played a pivotal role in the resistance against African colonialism and possessed remarkable foresight in inspiring Africans to pursue what he described as a “second liberation” from future forms of domination.

“There is no doubt that King Moshoeshoe was perfectly conscious of the fact that the British were colonisers in the same way as the Boers,” Mr Mbeki said. “After all, the Basotho under his leadership had fought off the British to avoid being colonised by them. It was a stroke of genius that King Moshoeshoe snatched victory from the jaws of defeat by persuading the British to proclaim his kingdom a British protectorate, thus saving it from becoming a Boer colony.”

He said such strategic leadership inspired numerous writings on King Moshoeshoe’s far-reaching influence.

Mr Mbeki cited a poem by Jonas Ntsiko, Tsohang bana ba Thaba Bosiu (Rise, children of Thaba Bosiu), published 13 years after King Moshoeshoe’s death, saying it captured a critical historical understanding among indigenous people of southern Africa during their resistance to colonisation in the 19th century.

“The guerrilla wars fought in many African countries during the 20th century to defeat colonialism and apartheid introduced into the global vocabulary the concept of a ‘liberated area’,” he said. “These areas provided a base for the continuation of the struggle for liberation.”

He explained that Basutoland, as Lesotho was then known, had become a liberated land for oppressed people across southern Africa, offering sanctuary and hope for the broader African liberation struggle.

“What the poet was saying is that Basutoland was, for the struggling people of southern Africa, a liberated land,” Mr Mbeki said. “And so when the poet said ‘tsohang bana ba Thaba Bosiu’, it was not an imposition on the people of Lesotho, but an affirmation of a role King Moshoeshoe himself understood and accepted — that a protectorate could not be an end in itself, but a liberated area meant to advance the total liberation of Lesotho and its neighbours.”

He added that colonial powers were fully aware of this role and “never forgave King Moshoeshoe for it”.

Mr Mbeki noted that King Moshoeshoe II later gained immense recognition, becoming the paramount leader of the people in Bloemfontein just two months after the formation of the African National Congress, and playing a critical representative role for African people as far north as Zambia.

He said the king never relented in his efforts to advance African liberation, consistently making his position known despite suffering two exiles under the regimes of Chief Leabua Jonathan and Major General Metsing Lekhanya.

Mr Mbeki said King Moshoeshoe II’s contributions to continental and global institutions, including the Organisation of African Unity and the United Nations, remain well documented and continue to inspire generations across Africa.