A NEW scramble for Africa is unfolding. But it’s no longer Western powers vying for land and the continent’s wealth as they had until the outbreak of World War I. The power struggle now is among Asian nations, most notably China and Japan.

This time around, the West is content to stand on the sidelines as Asia’s biggest powers duke it out to secure resources in the world’s final economic frontier. Unlike in the centuries past, however, there is no coercion or bloodshed. Instead, the race is on for Japan and China to woo Africa’s public opinion at large — not just the favours of investor and leadership class.

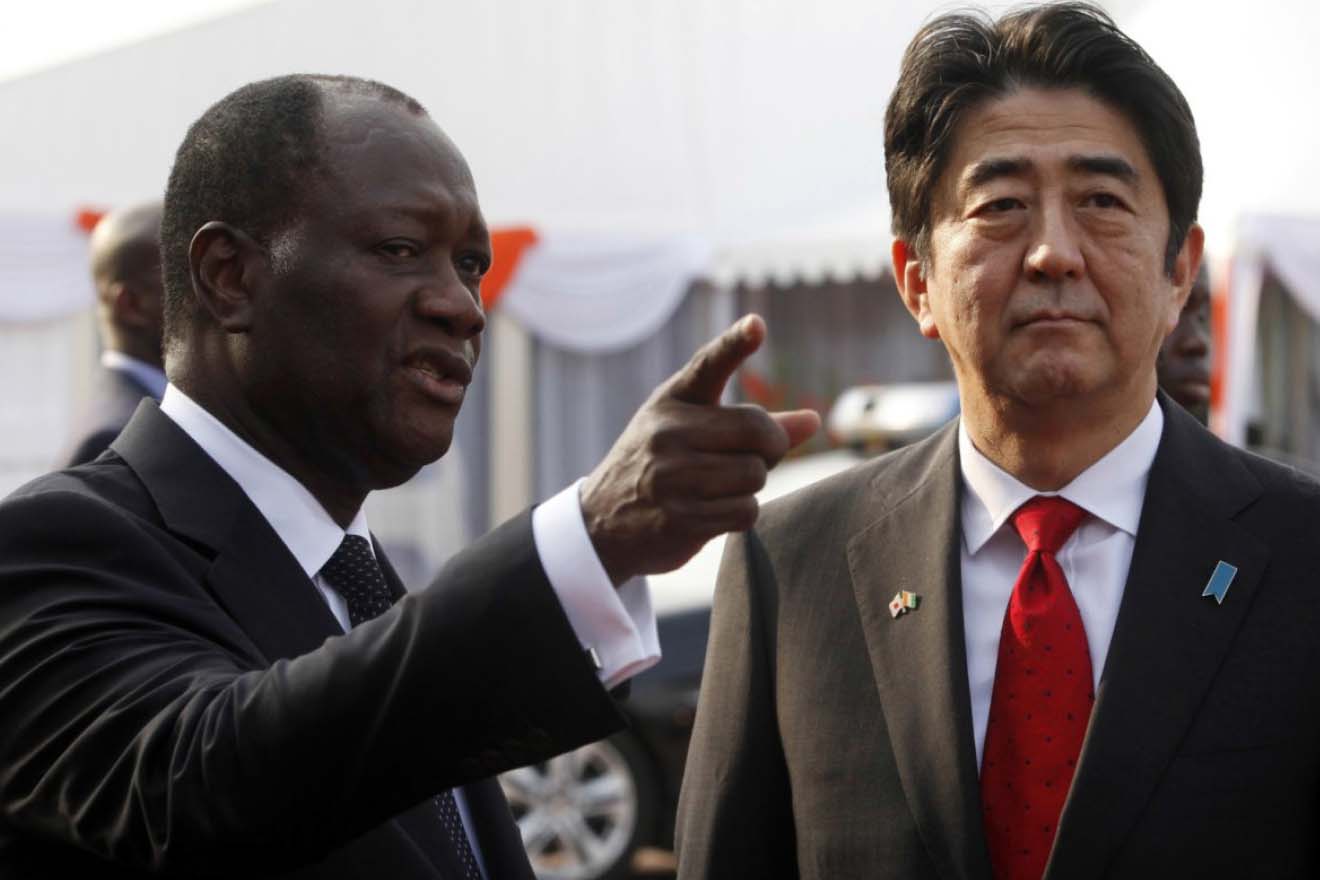

Japan’s latest effort concluded recently with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Africa in early January 2014. It was the first such visit by a Japanese premier in eight years, in contrast with the multiple marathon trips by Chinese presidents during the same period.

Of the countries Abe visited, Ivory Coast is a centre of commerce in its region and Mozambique is rich in natural gas and other assets. The Japanese premier also made sure he met with the Ivorian soccer team and Mozambique’s women basketball league. In Ethiopia, Abe not only delivered a speech at the African Union’s Addis Ababa headquarters, but he also made a point to meet with Ethiopian athletes, including marathon legend Abebe Bikila’s son.

The official point of meeting African athletes was to promote Tokyo’s upcoming 2020 Summer Olympic games. But it also served the promotion of Japanese sporting business interests, not least by distributing free Asics sneakers.

On the financial front, the visit brought announcements by the Japanese government to double the total amount of low-interest loans to the continent to US$2 billion (M22 billion) over a five-year period, having promised US$1 billion (M11 billion) in 2012. Meanwhile, last summer, Tokyo promised Africa a total of US$32 billion (M354 billion) in public and private funding. This amount included US$14 billion (M155 billion) in official development assistance as well as US$6.5 billion (M72 billion) to support infrastructure projects across the continent. Japan has also promised to train African experts on cutting-edge technology and engineering.

Clearly, securing resources in the longer-term is a priority for Japan, not least due to struggles to meet its energy needs after the shutdown of all 50 of its nuclear reactors since the March 2011 earthquake at Fukushima.

Amid growing geopolitical uncertainties, Japan also faces a challenge of meeting its other commodities needs. Indonesia’s recent decision to ban exports of nickel and bauxite, for instance, has hit Japan’s stainless steel producers particularly hard.

The surge in resource-nationalism is only expected to strengthen worldwide. That makes it all the more urgent for resource-poor nations like Japan to win over as many commodities-rich nations as possible.

In his approach to Africa, Abe seems to have hit all the right diplomatic notes since taking office just over a year ago. He managed to balance offers of financial aid, technology-transfer and investments with winning over public opinion.

It was a sharp contrast in public relations efforts compared to his tone-deaf approach to dealing with neighbouring China and South Korea. Those ties have only been aggravated further by the premier’s decision to visit Yasukuni Shrine, which commemorates Class- A war criminals as well as Japanese soldiers who died in action, only days before his Africa trip.

While the Yasukuni visit was largely dismissed by the mainstream African press, senior Chinese government officials for Africa have been quick to attack Abe’s outreach and Japan’s foreign policy ambitions at large.

China’s ambassador to the African Union, Xie Xiaoyan, publicly stated that Japan’s prime minister is becoming “the biggest troublemaker in Asia”. He added that Japan’s aid efforts to the continent were part of Tokyo’s “China containment policy”. Yet China remains the single biggest player on aid to Africa. It has committed over US$75 billion (M830 billion) to the continent since 2000, and Japan simply cannot match that figure, dollar for dollar.

Still, Beijing clearly has lessons to learn from Abe’s public relations success. The Chinese have come under attack for not giving back to the local communities that they invest in and do not offer enough jobs or train people in Africa, bringing many workers from China instead.

Meanwhile, international organisations have criticised Chinese state-owned companies for their labour practices in overseas mines. A Human Rights Watch report in 2011, for instance, attacked state-owned China nonferrous Metal Mining Group for violating labour laws and regulations “routinely”. For both Japan and China, the stakes for Africa are real, unlike the disputes over territories in the East China Sea. The latter are more about a clash of nationalist identities rather than a race for resources.

For now, though, Japan appears to have the upper hand in Africa, at least diplomatically. The real challenge for Beijing will be whether it can match Tokyo’s soft power approach to winning over African hearts and minds.

l Shihoko Goto is the programme associate for Northeast Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars in Washington, D.C., and a frequent contributor to The Globalist, where this article originally appeared.