In Lesotho’s most remote areas where gynaecologists and obstetricians are but an alien species, falling pregnant could be as risky as traversing the high country in the middle of snowy weather.

By Tsitsi Matope

MASERU-It’s like in a violent Western movie depicting the 19th century American frontier —a heavily pregnant woman who is obviously in labour, sits on a horse and her anxious husband, wearing his shirt inside-out, keeps urging the animal to move faster.

[kml_flashembed publishmethod=”static” fversion=”8.0.0″ movie=”http://lestimes.com/storage/2014/03/Tsitsiflash2.swf” width=”730″ height=”380″ targetclass=”flashmovie” align=”left” play=”true” loop=”true” quality=”best”/]

Yet this is no motion picture but a real scene in Thaba-Tseka—one of Lesotho’s forgotten frontiers renowned for both its scenic terrain, snow in winter and inaccessibility.

With horses, the most practical mode of transport due to poor roads and the rugged landscape, pregnant women have since become silent victims of the bleak terrain as accessing healthcare facilities is but hard-labour on its own.

Horse-riding could be taxing and uncomfortable even for those in the best of health. And for an expectant mother, spending hours on horseback as the animal traverses the difficult undulating pathways en-route to the faraway clinic is but an agonising and foreboding experience.

However, such an experience is not only commonplace in Thaba-Tseka but also other districts such as Mokhotlong, Qacha’s Nek, Butha-Buthe and Quthing. In these places the nearest clinic could be two walking days away.

Due to the elevation of the highlands, some more than 2 800 metres above sea level, the weather is also unpredictable, adding to the dangers facing the women in their battle to give life.

The Government of Lesotho has constructed and upgraded 46 clinics in the hardest-to-reach areas with the help of the American Government’s Millennium Challenge Account aid programme, but still for many pregnant women, accessing services on time remains a mammoth task.

As a result, the inaccessibility of services has forced many mothers to reduce the number of times they visit healthcare centres, with others only being attended to once and waiting to deliver at home. In some instances, some women give birth while on their way to the nearest but still too far clinic.

A decade ago the Ministry of Health outlawed traditional birth attendants who had for many years helped many women deliver at home.

This development has contributed to the weakening of the early community-based risk-identification system, while also fuelling maternal mortality in some remote villages.

This development has contributed to the weakening of the early community-based risk-identification system, while also fuelling maternal mortality in some remote villages.

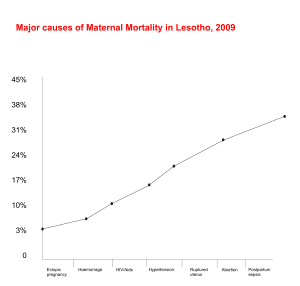

Lesotho has the highest maternal mortality rate, or highest number of deaths of women during pregnancy or shortly after delivery, in southern Africa. The Minister of Health, Dr Pinkie Manamolela recently said out of 100 000 live births, 1 155 women die due to pregnancy-related ailments.

“We are off-track in achieving the United Nations Millennium Development Goal 5 because one in every 32 women will die of pregnancy-related conditions. We have to put our heads together and find ways to effectively reverse this unacceptably high maternal mortality,” Dr Manamolela said.

The tragedy is that women in Lesotho are not only dying while giving birth at home but also in health centres. Investigations showed that the high number of deaths are due to the inaccessibility of health services, brain drain in the health sector with a high shortage of specialists such as gynaecologists and obstetricians to provide comprehensive maternal health services, backyard abortions, the inability of 70 percent of the facilities to provide labour and delivery services on a 24-hour basis and inadequate blood transfusion services at all hospitals and filter clinics.

HORSES AND DONKEYS TO THE RESCUE

‘Malehlohonolo Maluke’s husband Teboho narrated how worried he was on 12 February 2014, when his wife announced that she was in labour. Travelling more than 40 km from their village in Matsaile to Ha- Mokoto Clinic in the Thaba-Tseka district is no easy task.

Ha-Mokoto Clinic is one of the 14 clinics built in the remote villages of Thaba-Tseka district. Others are Sehong Hong, Linakeng, Aurey, Mt Matre, Lephoi, Popa, Mohlanapeng, St Theresa, Bobete, Kuebunyane, Manamaneng, Methalaneng and Semenanyane.

At Ha-Mokoto Clinic, which this news crew visited, solar energy is used for lighting while gas-fridges are used to store vaccines. Laundry is sent for dry-cleaning to a facility in Thaba-Tseka town, which is about 50km away.

During winter months, the solar system does not function due to inadequate sunlight and the nurses use candles to deliver babies at night.

There are three midwives and two nursing assistants working at the clinic. Mothers who suffer complications are referred to Paray District Hospital, which is more than 50km away, and the ambulance can take hours before it comes to take the suffering women away.

Mothers are attended to by a medical superintendent, who is neither a gynaecologist nor an obstetrician.

And this is the norm at most district hospitals. Cases that cannot be handled at district-hospital level are referred to the Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital, a national referral facility in the capital Maseru.

Mothers who make it alive or live after they are attended to in Maseru are considered lucky.

“I thank God that we made it on time,” Teboho, Maluke’s husband said.

The 26-year-old Maluke, who is now a mother of four, said travelling on a horse while in labour was such an ordeal.

“This is my last child. I cannot continue riding horses to visit the clinic each time I am pregnant. Although this is the only mode of transport my family could afford, it’s not safe, I can fall because the roads are bumpy and at times, during all my four pregnancies, I had to ride at night to make it early at the clinic,” Maluke said after she gave birth to her bouncing baby boy. The same horse that brought her also carried mother and baby back home.

Matsaile is the furthest of the 13 villages, which accommodate more than 5000 settlers served by the clinic. The villages are haphazardly scattered around the mountain ranges. The roads to the clinic are punishing and in some cases, there are no roads to even talk about.

During Lesotho’s notoriously cruel chilly winters, the whole district is covered with snow and travelling in the slippery mountains can be extremely dangerous.

Questions have been asked in some quarters why residents should not be relocated to areas much closer to civilisation.

However, villagers in these mountainous districts are livestock-farmers who produce large quantities of wool and mohair and are, most of the time, at peace with their environment. They stay because of the abundant water and pasture for their livestock, they say, with the major headache coming when pregnant women are in need of health services.

Maatang Moseli, 28, is three-months pregnant. She has just arrived at Ha-Mokoto Clinic on horseback from her village, Ha-Moliehi, which is about 15km away.

It took her three hours to reach the clinic and by the time she came off the horse, she was struggling to walk.

“My father-in law taught me how to ride horses to make it easy for me to go to the clinic, especially when I am pregnant,” she said.

Moseli is a mother of a boy aged four and each time she is visiting the clinic, she has to commit the whole day to the clinic business.

“I leave home as early as 4am and I am usually here by 7:30am waiting for the clinic to open at 8. Riding a horse is hard work because you have to know how to control the animal, otherwise it can get spooked and throw you off. It’s hardest and painful when I am riding downhill. I feel a lot of pain in my back, abdomen, around the pelvic and thigh areas. When I get home late at night, at times after 8pm, I can hardly walk and I also experience excruciating bodily pain,” she said.

Moseli said a few families in the area had tried innovations such as carts drawn by horses or donkeys, to ferry the pregnant women to the clinic.

“This cannot work here because the roads are just too bad and the carts won’t last. The other thing is that you can’t transport a pregnant woman in a cart because it would be so bumpy and unbearable. We prefer riding slowly because with the reins in your hands, you can control the speed of the horse,” Moseli said.

The Nursing Officer and midwife at the clinic, Monica Mahaso however, said it was not advisable for pregnant women to travel on horses.

“The distance travelled is too long and being on a horse in such a state is uncomfortable. It also strains both the mother and the baby. We usually struggle to get the foetal heartbeat when we are examining such mothers. A strenuous exercise can also cause premature deliveries and miscarriages,” Mahaso said.

Another woman, Marenang Ntlheng, 37, is six months pregnant and has been riding a horse from Ramatseliso Village to Ha-Mokoto Clinic with her two previous pregnancies. It takes her two hours from Ramatseliso, which is more than 30km away, although other women can take four to five hours.

“I take two hours because I am an expert at horse riding unlike other pregnant women who are afraid that they might fall,” she said.

Ntlheng said despite her skills, which she learnt from her husband, each time she is on a horse, she feels abdominal pains.

“A day after returning from the clinic, I feel a lot of pain in my back and shoulders,” Ntlheng said.

She rides the horse to the clinic until her pregnancies are eight months old before she resorts to walking.

“When I am in such an advanced stage of pregnancy, it is hard for me to go up the horse. I can walk for five hours from my village to the clinic.”

However, for other women such as ‘Mabatho Marumo, owning a horse is such a blessing.

Five months into her first pregnancy, Marumo, who is also from Ramatseliso village walks to Ha-Mokoto once every month.

“Walking is hard. Maybe if my family could afford a horse, it would make life a bit easy for me,” Marumo said.

“I have to come because I am often sick. On the way, I take a rest and eat and drink water which I carry from home. The load I carry slows me down but what choice do I have?”

Marumo looks wasted and it is unimaginable that she would walk back home with signs that she is weak and the clouds look pregnant with rain.

“If it rains, I might ask for a place to sleep at any of the villages on my way home and continue the journey home the following morning,” she said before breaking down in tears. For minutes, nothing could console her.

The clinic midwife, Monica Mahaso, said although the clinic staff felt for Marumo, they were unable to accommodate her in the clinic’s waiting mothers’ lodge.

“Due to her health status, which we cannot reveal, we cannot allow her to stay here because we are unable to manage her condition. We have to refer her to Paray District Hospital where she can stay in the waiting mothers’ lodge and be monitored by specialists who understand her condition,” Mahaso said.

She explained the other issue was that not all mothers were comfortable staying in the mothers’ waiting lodge.

“Some have children and they have noone to take care of them while they wait to deliver.”

Until this year, the mothers were also required to bring their own food.

“Beginning this year, the situation has changed; with the help of the World Food Programme (WFP), we are now giving them some food. We hope this will encourage some mothers to stay in the lodge while they wait for safe delivery here.”

Butha-Buthe women’s worst nightmare

Butha-Buthe is a district in great need of baby-delivery services. All clinics in the district’s rural areas do not deliver babies and pregnant women have to travel to Butha-Buthe town. But this is not always the case and many women deliver at home.

The Butha-Buthe District Hospital, Seboche—a Roman Catholic facility— and St Pauls’ Clinic, are the only health-centres that provide baby-delivery services.

As a result, the bulk of mothers would rather travel to the clinics just for antenatal or pre-birth care. The modes of transport are horses, donkeys and in worse situations, heavily-pregnant mothers are carried on makeshift wooden stretcher-beds. Just like in Thaba-Tseka, some mothers also walk long distances.

Sick, pregnant mothers living on the plateaus are often carried on the wooden-beds down to the main road before they are made to ride horses or walk to the clinic if they can.

There are three clinics situated in the hardest-to-reach areas, which are Ha Motete, Rampai and Boiketsiso. During this investigation, all these were inaccessible because of the heavy rains.

However, Linakeng Clinic, although not classified as hardest-to-reach, is inaccessible with any other type of transport apart from a four-wheel-drive vehicle, donkeys, horses or on foot, and serves six villages of about 7000 people.

Damaseka and Ramabeleng are part of the villages that also rely on Linakeng for health services.

The clinic is located 15km away by gravel road and it is much further for those living on the plateaus and mountains.

Damaseka village chief, Kopano Mothuntsane said his village was willing to contribute money and construct a small clinic that can provide health services that include delivering babies.

“Most mothers in this area suffer a lot of stress when they are pregnant because both the Linakeng Clinic and Butha-Buthe hospital are too far,” he said.

Butha-Buthe Hospital is about 25 km away from Damaseka village.

“We are trying to convince the government that we are willing to help with the construction of a small clinic here if they can provide nurses. We have since collected stones and grass to show our commitment to contribute towards the construction,” Chief Mothuntsane said.

Although traditional birth-attendants or midwives are no longer as active as they used to be in the area, Mothuntsane said it would be foolish for the communities to just allow the traditional caregivers to fold their arms when someone should be helping mothers deliver at home.

“Many mothers here only manage one or two clinic visits. It is unrealistic for them to make it to town when in labour and in many cases at night. We have a gravel road here, which can just disappear and resurface metres away. It’s not safe to have a heavily-pregnant woman walk or be on a horse that far on such a poor road.”

Some women in Damaseka village said because of the hardship associated with accessing services and risks involved, they would rather not have more children.

There were unconfirmed reports that last year, two mothers died of birth-related conditions in the six villages under Linakeng clinic.

‘Masepeame Ramabeleng, a 96-year-old woman living with her family on Ha-Tlehi Mountain, said it was strange how pregnant mothers still struggled to access services in the area.

“I delivered seven children at home during my time and there was no clinic. Although we relied on herbs to be strong, some mothers still died due to pregnancy-related ailments. I have also watched my daughter-in-law deliver all her 12 children at home because the clinic is too far,” Ramabeleng said.

However, Butha-Buthe Hospital, where the bulk of the mothers who can manage travelling to town deliver, has its own challenges.

In an interview, the hospital’s senior nursing officer, ‘Majulia Seutloali said the hospital lacked the capacity to save the life of every mother who suffered various complications.

Last year, five mothers died at the hospital from pregnancy-related complications. She said it was possible that more die at home after they have been discharged from the hospital, which has no follow-up system.

“Sometimes, we later hear that a certain mother who had just delivered here, died at home and was already buried. We have no way of following-up the mothers we would have attended and the families also don’t report when someone dies soon after giving birth,” Seutloali said.

The hospital has no obstetrician to enhance the care given to mothers when pregnant and after they deliver. “We also don’t have a gynaecologist to help deal with infections that can occur before and after delivery,” Seutloali said.

In some cases, the hospital has no blood to save mothers who would have suffered heavy bleeding before and after delivery.

On average, the district hospital assists 200 mothers deliver per month and Seutloali said this was too high considering the shortage of midwives and incapacity to accommodate all mothers.

The maternity ward can only accommodate 20 mothers and as a result, two pregnant mothers can share one bed. Although the hospital has 24 trained midwives, only four are assigned to the ward in the afternoon and another four in the evening while the other 16 work in other wards.

“This does not mean that at any given time, we have four midwives in the maternity ward because some can be off-duty and the pressure to serve all the mothers becomes high.”

The curse of motherhood

That many mothers have a chill down their spines each time they imagine what could happen if they decide to fall pregnant is a reality in Lesotho. ‘Mamarake Ranku, 28, is such woman who said she would never forget how her neighbour, the late Tlotliso Tsikoane, 32, bled heavily before she died hours later at the Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital on February 9, 2014.

That many mothers have a chill down their spines each time they imagine what could happen if they decide to fall pregnant is a reality in Lesotho. ‘Mamarake Ranku, 28, is such woman who said she would never forget how her neighbour, the late Tlotliso Tsikoane, 32, bled heavily before she died hours later at the Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital on February 9, 2014.

“What really pains me is the thought of the difference it might have made had a doctor at the hospital had admitted her right away when I took her there on Saturday morning (8 February),” Ranku said.

Tlotliso Tsikoane was a single and physically disabled woman who worked in the Thetsane area factories in Maseru. The pregnancy that killed her was her second.

Her story is one of the many told in Maseru of how, in some cases, women in labour are turned away, maybe in some cases, because they had not been referred to the hospital.

Some of these mothers later die.

Tsikoane, who was 40 weeks pregnant, died after undergoing an operation that saved the life of her 2.780kg second son. Her first son died when he was two years old, a few years ago.

Tsikoane’s neighbour, Ranku said although she took her to the hospital heavily bleeding, the doctor who attended her prescribed some drugs and told her to go back home.

Upon arrival at home, Tsikoane spent the day in bed and bleeding.

“At around 5pm, I realised she had deteriorated and decided to take her to a nearby clinic, Qoaling. Upon arrival, the nurses realised she was in labour and immediately referred her to Queen ‘Mamohato Hospital. Despite her state, we had to use public transport since there was no ambulance.”

At around 7pm, Tlotliso was admitted in Ward J. “That was the last time I saw her. When I visited her the next morning, she was gone.”

The late Tsikoane’s brother, Lekhafola, said the family suspects their daughter died as a result of negligence.

“When she came the first time, they should have helped her. They told us what killed her was cardiac-pulmonary arrest but what caused it ?, ” Lekhafola said.

The Director for Operations at the Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital, Dr Karen Prins said the hospital was very disturbed by the tragic outcome.

However, Dr Prins said returning patients in the latent phase of labour was common.

“The patient was not anaemic and therefore, there is no substantiation that the patient bled heavily before the delivery.”

She said preliminary investigations showed the late Tsikoane had a pre-existing medical condition that was the direct result of her untimely death.

“Although she already had this condition during her first caesarean section, it must have deteriorated significantly before the second pregnancy.”

Dr Prins said two additional clinicians were called from home to assist while additional staff on site were also called in, in an attempt to save her life.

“We have offered to have an autopsy done by an independent forensic pathologist to confirm the cause of death,” she said.

However, Tsikoane joined a list of mothers who could access health services but still ended up dead, sometimes leaving their babies.

‘Malerato Marasi from Teyateyaneng in the Berea District cannot forget the last words her daughter-in-law, the late Mpolokeng Tsoelipe Marasi, said after undergoing a caesarean section.

“She said ‘I can’t bear this pain anymore, I fear for my children, my baby’,” Marasi said.

“What comforts me is the grandson she left me. Mpho (meaning Gift) is eight-months-old now. I wish she was here to see him grow. He is so handsome.”

The late Marasi, a TK FM radio producer and presenter, also left another son aged four. Her baby was only five-days-old when she died two days after the caesarean section.

“There is nothing we can do to bring her back; I wish there was something.”

The late Marasi went to the hospital after complaining of abdominal pain. Her mother-in-law said a day later, she underwent a caesarean section to remove the baby.

“She had an abdominal pregnancy and hospital officials told us another procedure had to be done to remove the placenta. They also explained that it was not an easy procedure because the placenta would be attached to any part of the body.” After the operation, she suffered heavy bleeding.

“Some family members donated two pints of blood but it was already too late to save her. She died two days later,” Marasi said, adding what disturbed her was that the doctors had failed to detect that her daughter-in-law had an abdominal pregnancy, on time.

“We did not know until when they had to operate her.”

When hospitals cannot save pregnant mothers

However, the Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital director of operations, Dr Karen Prins said failure to access services in some areas, inadequate skills, lack of education, poverty and cultural practices are generally some of the factors sending mothers to an early grave.

“It is critical to identify and address all the barriers that limit access to quality maternal health services to be able to improve services. This would enable policy and lawmakers to make informed decisions on the impact of some of the laws that have a direct effect on maternal mortality. For example, legalising safe-abortion and quality post-abortion care should be considered to save the lives of women relying on unsafe backyard abortion services,” Dr Prins said.

She said between October 2011 and June 2013, 47 mothers died at Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital.

However, some of these mothers who died were referred to the hospital from the country’s 10 districts, including filter clinics in Maseru. According to Dr Prins, out of the monthly average of 400 to 450 deliveries, there are 40—50 referrals.

“The majority of these cases, in average 19.4percent of all deliveries, end up as caesarean sections due to the complicated nature of the referrals,” Dr Prins said.

She said during the 20-month period (October 2011-June 2013), the highest killer of mothers was pregnancy- induced hypertension (pre-eclampsia and eclampsia) contributing 33.9percent of deaths.

Maternal deaths due to post abortal sepsis were 20.7percent, 16.7percent due to medical causes predominantly HIV and AIDS-related, 15percent due to haemorrhage while other causes include puerperal sepsis, uterine rupture and abdominal pregnancies, she added.

“It is important to understand that despite a high mortality rate in Lesotho, in 2013 we reduced maternal mortality by 57percent.”

Despite the reduction, she said there was need to continue improving the referral system.

“In Lesotho, we have a basic patient pathway that starts from the village health-worker and moves up progressively to the community health-centre, the district hospital and to the national referral hospital. However, several components of the proposed referral system are not working as expected. A lot of patients refer themselves to the hospital and these self-referrals negatively impact the provider-patient ratio,” Dr Prins said.

She added there was need to capacitate healthcare workers at district level so they could deal with basic surgical interventions to prevent unnecessary referrals.

“Although there is always need to recruit more specialists, including at Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital, Lesotho, being a nurse- driven health system, has even greater need to capacitate midwives in basic emergency obstetric-care as well as training general practitioners basic surgical interventions.”

To significantly reduce maternal mortality, Dr Prins said every woman should access antenatal care in pregnancy, skilled care during childbirth, care and support in the weeks after child birth.

“It is particularly important that all births are attended by skilled health professionals as timely management and treatment can make a huge difference between life and death.”

She explained it was also vital to prevent unwanted and early pregnancies.

“All women, including adolescents, need to access family planning services to prevent unplanned pregnancies that can lead to risky backyard abortions.”

The Director for Nursing Services in the Ministry of Health, ‘Makholu Lebaka, on her part, said over the years, there has been a number of strategies the government has employed in an effort to reduce maternal mortality.

However, the upward trend in maternal mortality, she said, showed there was need to review the current strategies and introduce new interventions in order to make positive impact.

During the decentralisation process of the primary healthcare services currently underway, initiatives such as the boosting of nurses from two to five, (three midwives and two nursing assistants) at all clinics in the districts were introduced, Lebaka said.

Nurses and nursing assistants (230) working in the 46 hardest to reach health centres are also expected to before April this year get incentives that include furnished accommodation, monthly hardship allowances of M600 and transport allowances of M250. The move is meant to make working in these hard to reach areas, shunned by many care providers, attractive.

However, it is yet to be seen whether this would improve maternal health.

She added the Mother-Baby Pack initiative also introduced a few years ago to provide medicines and other medical necessities to pregnant mothers living in areas far from health centres, was also one of the several strategies.

Lebaka said Lesotho could learn from models that have worked in other African countries such as the Private Nurses and Midwives Association of Tanzania (PRINMAT), a Non-Governmental and non-profit-making organisation comprising of registered nurses and midwives.

“We can replicate models, which include the PRINMAT. This initiative has seen private nurses and midwives coming together and setting-up community facilities in remote areas, in the middle of nowhere like what characterise many of our areas. These centres provide reproductive health-services at small community maternity homes throughout Tanzania. What is important about this initiative is that it is also supported by the government to ensure sustainability,” Lebaka said.

Tanzania’s maternal mortality is at 460 per 100 000 live births. The PRINMAT programme was established in 1999 following the realisation that maternal deaths and complications were high in the majority regions of Tanzania.

In the case of Lesotho, Lebaka said interventions should respond to mainly the country’s challenging topography and also be able to address and deal with the dynamics associated with the process of giving birth.

“Our interventions should be well-informed by the situation on the ground. We need to understand that when it is time for the baby to come, it cannot wait for skilled personnel or for the mother to reach a faraway health centre on a horse. That is why we need to strengthen community-focused and orientated healthcare developments.”