Makatleho Mohapi

MOHALE’S HOEK-The beauty of Ketane in Mohale’s Hoek is enchanting as it is an embodiment of this rolling district.

Springs keep the environment nourished and Telle Primary School students, their teachers, and indeed the rest of the community, happy.

Even in these hard times of the El Niño-related drought, this is one of the few local schools which kept its pots filled with a variety of fresh vegetables and its students well-fed.

Telle Primary School, which is situated just above Ketane River, is a unique institution which has demonstrated that with an agriculture-inclined management system, learning facilities could grow their own food, develop and significantly complement diet provided by government in partnership with the World Food Programme (WFP).

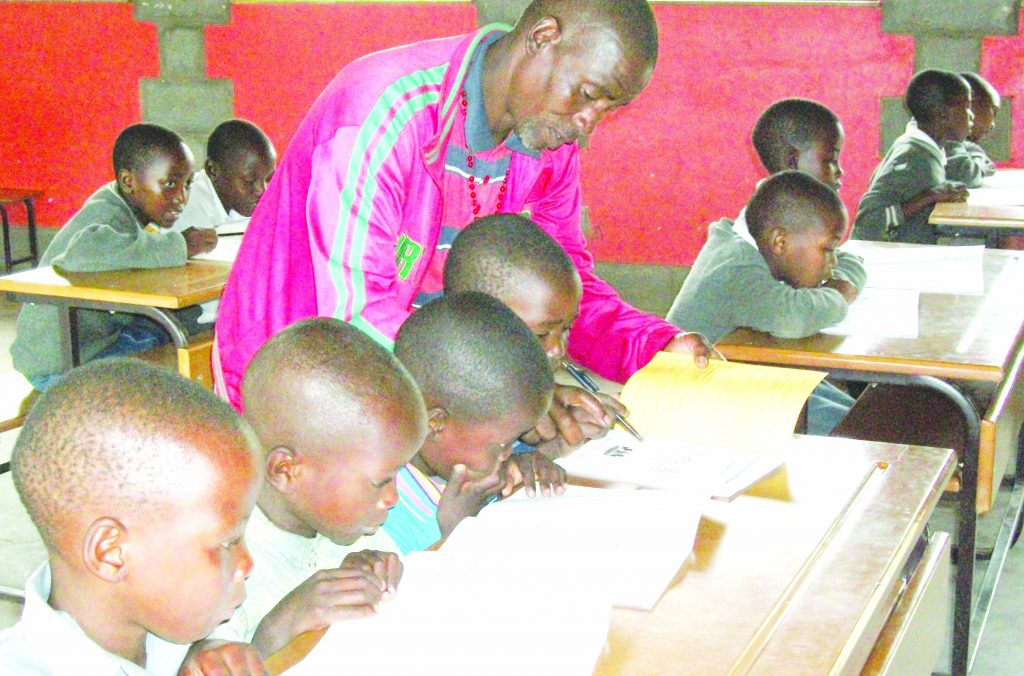

The school offers education with a difference as demonstrated by massive vegetable production since 42-year-old Motlatsi Mothae took over as principal in 2004.

His passion for food production has seen the eight teachers at Telle imparting agricultural knowledge to their students and ensuring they play a leading role in growing beetroot, carrots, cabbages, spinach, tomatoes, leek onions, butternuts, fruits and maize.

Telle Primary School has a lot to brag about—the students eat two vegetable meals per week and at the end of each term, still find themselves with some surplus. Two months after the first term commenced in January, students at the school are still eating fish they received from WFP in 2015.

Through interaction with the school authorities, WFP realised Telle Primary had much more to offer its students apart from the regular syllabus, and in 2011, the humanitarian organisation donated two greenhouses and irrigation equipment through the globally commemorated Walk the World Against Hunger fundraising activities held each year in June.

Mr Mothae says following the donation, life has never been the same at the school. Apart from being a school of choice in the district, the greenhouses have made Telle a leader in teaching students protected food production and irrigation technologies, in addition to boosting the production of high quality vegetables.

“The students are learning a lot from the production in the greenhouse. We have employed a gardener to work fulltime in the greenhouse while the students concentrate on production outside the conservatory,” says Mr Mothae.

While the greenhouse produce is irrigated by spring water through drip-irrigation technology, the students fetch water from the same spring to irrigate the other gardens in different parts of the school.

The school is using the trench conservation technique that allows deep furrows to harvest water for later irrigation of the rich gardens.

“We have the capacity to increase our production and can even supply some neighbouring schools and also sell in Mohale’s Hoek town provided we are assisted with transport. The soil here is rich and there is plenty of water,” says Mr Mothae.

He explains the importance of helping children understand food comes from the soil and people have to work in order to eat.

“For me, there is nothing as empowering as the ability to produce your own food and becoming self-sufficient.”

Mr Mothae says plenty of food also encourages cooks at the school to become innovative. This year the school employed four cooks—three women and one man.

“I have seen that they are going all the way to make the school meals appealing,” says Mr Mothae.

After cooking peas, they also prepare tomato and leek soup to make the pulses tastier. Beetroot is also added to the green vegetable dishes including the pumpkin relish. The 306 students who include 109 orphans and vulnerable children also eat apples, peaches, butternuts and corn when they are in season, making Telle the envy of students from neighbouring schools. And after feeding themselves, they still have plenty of food to sell to the local community. Over the years the school has generated enough money to construct five accommodation facilities for the teachers. Lack of accommodation is one of the challenges discouraging qualified teachers from working in some remote parts of Lesotho.

Yet despite the joy on the foot of the mountains, all is not well on top of one of the many mountains surrounding Telle Primary School.

Students at Ntamaha Primary School appear to be in a world of their own. A total of 33 students transferred from the school this year, leaving the institution with only 12 learners and one teacher. In fact, the school used to have two teachers but one of them resigned last year. The Ministry of Education and Training established the school in 2003 to cater for children living on top of this mountain who used to struggle to access education. A secondary school was subsequently established at the same premises in 2007. Unlike Telle Primary School, there is no garden and mouth-watering vegetable dishes served at Ntamaha Primary School. The only teacher at the school, who is also Acting Principal, Matsa Monaheng, says they cannot establish a garden due to the livestock which occasionally graze in the schoolyard.

“It is for that reason that I do not get along with the local community and can’t also stay in accommodation facilities provided by the school,” says Mr Monaheng.

Lessons start at 9am and each morning, Mr Monaheng walks about 15 kilometres to school from his home below the mountains in Ha Ntseene village. The students, who are in classes one, three and four, then sit according to their classes, ready to be taught by one teacher. A class four student says she is pleading with her parents to transfer her to another school where there are enough teachers. “We are only two in my class and being taught the same things the class three students are taught. I feel cheated and know that I am wasting my time coming to this school,” she said.

Mr Monaheng confesses the quality of education is seriously compromised as he is not trained to teach more than one class at the same time. “The slow learners are bearing the brunt of this unfortunate situation because there is no time to give them much attention,” says Mr Monaheng. The father-of-eight says he is doing his best to help the students while he waits for the Ministry of Education to deploy some teachers to the school.

Some of the villagers say they had to transfer their children because they were unhappy with the way the school was being run.

“We asked for a school to be built here but are disappointed that the priority has never been education but power-struggles between the teachers to the extent that the other teacher had to resign,” one of the parents said.

“We know that when Mr Monaheng is attending meetings or workshops, the poor students only come to school to play and eat,” another parent added.

But the cook, Tsietsi Tsoeu, has a different concern.

“If this school runs out of food, these remaining students might also leave. And if that happens then it means losing the little salary I am getting,” says Mr Tsoeu.

The villagers, who used to collect WFP food using their donkeys for a fee from Telle Primary School, are yet to collect the consignment for the first quarter and Mr Monaheng says this is in reaction to the late payment of their claims submitted last year.

An Education Officer based in Mohale’s Hoek, Ms Palesa Ramonate, confirms receiving complaints regarding the situation at Ntamaha Primary School early this year.

“We will soon take action aimed at resolving the challenges, including deploying at least two teachers to the school,” says Ms Ramonate warning that finding teachers willing to work in hard-to-reach areas is not easy.

She explains it is unfortunate students remaining at the school are not receiving quality education while others were forced to transfer due to management challenges.

“There are other primary schools in the remote parts of the district which are also being run by single teachers. This is an unfortunate situation which also worries us. A school should at least have three teachers,” she said.

She explains starting this year, the district education office would intensify the monitoring schools in the remote areas to ensure their management is above board.

“We would like to prevent challenges that may lead to massive student transfers or loss of teachers the way things happened at Ntamaha Primary School,” she said.